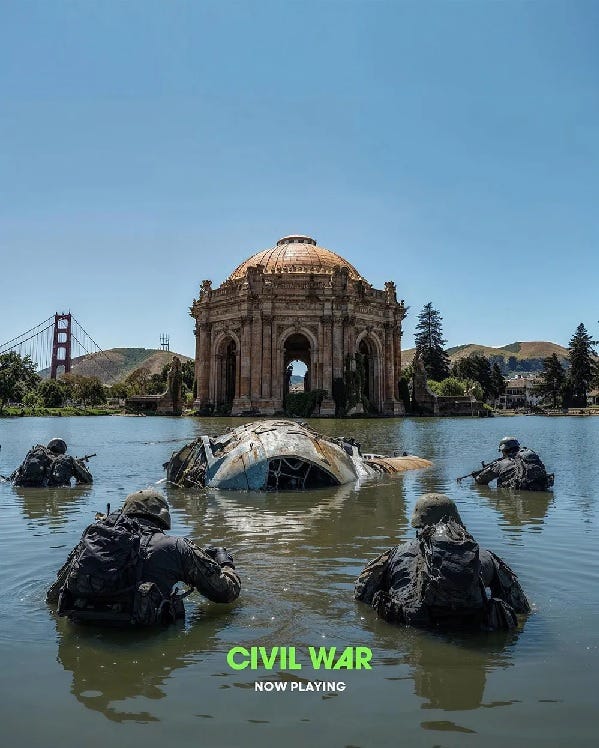

The new movie Civil War has garnered all kinds of buzz—though I’m not sure either “garnered” or “buzz” are the right terms for the discourse the movie has produced. Most of the discussion has revolved around comments made by the filmmaker and actors in press interviews—the movie itself doesn’t have that much to hold on to; there’s nothing worth debating. And “garnered” feels off because the chatter doesn’t feel earned but intentionally and sometimes shamelessly provoked, most recently by a string of advertisements mocked up with the help of AI that show various well-known landscapes around the United States picturesquely left in ruins, even though those specific depictions are not in the movie itself. This ham-handed campaign confirms what I argued in an essay for Slate about the movie (and its historical antecedents): the film takes advantage of our fixation on the possibility of political violence without actually bothering to say anything interesting or useful in the process:

For all the ear-splitting explosions and hair-raising exchanges of gunfire across a variety of modern American landscapes—and, yes, the IMAX experience is intense—the film seems to be conscious of its own essentially pornographic nature. There is something cheap and unseemly in the way the camera lingers on a pile of human bodies, or the Lincoln Memorial blown to smithereens. Just as Southern secessionist Edmund Ruffin found writing gory scenes of executions and massacres “conducive to immediate pleasure,” Joel, one of the war photographers in Civil War (played by Wagner Moura), looks out on a night sky filled with arcing mortar shells and grunts, “This gunfire is getting me so fucking hard!”

The viewer is meant to be implicated, and we are. But instead of any profounder meditations on why mass slaughter both attracts and sickens us—for even Joel is eventually reduced to a puddle of tears—the film offers 90 more minutes of picturesque wreckage, bone-chilling executions, and, finally, the eagerly panted-after “money shot” (a phrase one of the journalists actually uses as the film’s climactic scene unfolds). At least Ruffin had an excuse for pleasing himself by turning his fantasies of American carnage into art: He wanted to bring it about. Garland claims he wants his film to do the opposite, but it’s strange, then, that not a single line or moment even implicitly alludes to what if anything could have been done to keep things from reaching such a breaking point.

I do think it is a good thing, and argued as much in my book, for Americans to wake up from their long exceptionalist slumber and to recognize that all the disorder and mayhem we have witnessed in other faraway countries—and sometimes caused, other times exploited—could someday happen here. After January 6, this seems a much less provocative point. The movie struck me as vapid and lazy, half-baked and risk-averse.

I was pleased to see the New Yorker’s estimable Andrew Marantz land on a similar analysis of the film’s shortcomings, and even more pleased to read the final paragraph of his piece:

This was satisfying to read, not least because I admire Marantz’s work, but also because it suggests the book, nearly four years after publication, still has something to say about the country’s ongoing predicament.

More proof in that regard is the news I recently received that Break It Up will finally be published in paperback in November, just a week or so after the presidential election. In sitting down to write my preface in the coming weeks, I find myself in a similar position to when I first sent the book off to the printers, in the spring of 2020: I have no idea what the world will look like the day this next edition sees the light of day. Whatever happens, I seriously doubt it will look like this—

—even if it would sure be good for sales.

I have been a bad, a very bad newsletterer these past months, mostly because I’ve been hard at work finishing revisions on my next book. FEAR NO PHARAOH: American Jews, the Struggle to End Slavery, and the Civil War will be published around this time next year (shortly before Passover). I’m really pleased with how it turned out and can’t wait to share it with you all. I’ll update with more details—the cover, exact pub date, and pre-order link—when I have them.

I’ve also been writing a lot more on the side—including for local Hudson Valley publications, which as I spend less time on social media and the internet generally I find greatly rewarding. For Chronogram, a delightful monthly based out of Kingston, just upriver from me, I wrote a long report on the Fjord Trail, a proposed walk-and-bike path between Cold Spring and Beacon, my adopted hometown. The plan, largely funded by one wealthy local resident (who I surprisingly managed to get on the phone), has sharply split the local community, especially in Cold Spring, between those who see it as an attractive solution to problems related to over-tourism and those who think it will only make such problems worse. While I’m personally excited to see the trail completed and be able to bike with my kids to Cold Spring for ice cream, I see the merits of both arguments and feel that both sides, in different ways, have gone about making their cases in somewhat unhelpful, even disingenuous ways. I massively enjoyed reporting and writing this piece. Having sat behind my desk for much of these past few years working on one book and then another, I’d forgotten the truth I learned from a wizened old scribbler I met in college: journalism is the most fun you can have with your pants on.

I also wrote two book reviews for Chronogram—unusually, for me, they were reviews of works of fiction, both by Hudson Valley authors. One novel I rather liked (so did James Wood), while the other I sadly did not. (Oddly, the author of the first one blurbed the second one as “the Great Gatsby, updated,” which is nothing less than blasphemous.)

Somehow I managed to parlay my growing interest in local history, which I think I wrote about here before, into a pretty sweet gig writing a short monthly column for Hudson Valley magazine. My “Backstory” pieces will appear on the last page of every issue starting this June. For the first piece I wanted to wind the clock back as far as I could—oh, about 385 million years. It’s about the discovery in the Catskills a few years ago of the oldest tree fossil ever found on earth. For future columns I’ve got a long and growing list of ideas, from lesser-known Hudson River School painters to Revolutionary War lore and much else.

(One item on that list was a brief history of the various earthquakes this region has experienced over the past few hundred years. Too late! I felt the 4.8 magnitude quake here in my basement office. The walls rattled a bit. I thought it was the oil truck outside refilling our tank. Still, I felt it. Always wanted to experience an earthquake—though not nearly as long as the great science and nature writer John McPhee, whose book In Suspect Terrain, about the geology of the Appalachian Mountains, I’ve been reading in fits and starts for a few months now. The Princeton-residing McPhee, who can make the otherwise most agonizingly boring details of fault-lines and orogenies as exciting as, well, whatever the word “orogeny” calls forth to your mind, had somehow gone ninety-three years without ever having actually felt an earthquake. Is it strange that it actually makes me happy, even weeks later, that now he has? This is the power of his writing.)

Other than the local stuff, I published two book reviews in the fall: one in the Washington Post on a new book about the Underground Railroad, and another in Slate on a new biography of the Confederate general James Longstreet, who embraced racial equality and the Republican Party after the South’s defeat in the Civil War. Here’s a little from that:

For the only prominent Confederate who switched sides for that second fight—thus earning himself not one, but two, lost causes to mourn—the reversal of Reconstruction was almost too much to bear. Ousted from office, Longstreet took refuge in relitigating his Civil War record, contending in interviews, essays, and eventually a mammoth-sized memoir, against uncontrite ex-rebels who wanted to pin the blame for the South’s military defeat on the man who had also brashly disavowed its essential ideas. As it is today, arguing over the Civil War was then another way of doing politics: Longstreet hoped that emphasizing the military aspects of the conflict would eventually cool the sectional animosity that had brought all the bloodshed in the first place.

When the Supreme Court ruled in January that federal agents could remove barbed wire installed by Texas along the southern border with Mexico, Governor Greg Abbott invoked what he called “Texas’s constitutional authority to defend and protect itself.” Republican-led state national guard units and hordes of beefy militiamen streamed south to support the Lone Star State’s stand against the feds, some clearly hoping the twenty-first century’s Fort Sumter moment was finally approaching.

Just as that confrontation was building, a new poll from YouGov showed that roughly one in four Americans support their state seceding from the Union. Secession was most popular in Alaska, where 36 percent of respondents support secession, and least popular in Connecticut—fittingly, the Constitution State—where only 9 percent support independence. (Still seems quite high, no? Who are these people?) Vermont was excluded from the poll because not enough people from there responded. It’s a notable omission, as support for independence in Vermont likely rivals that of Alaska. Regardless, the two likeliest states to secede remain Texas and California, where secession polls at 31 percent and 29 percent respectively.

To be sure, support for secession in many cases remains simply an expression of partisan discontent, a way to blow off steam—or else why would more Republicans than Democrats wish to secede from the Union, even those who live in heavily Democratic-leaning states?

Does any of this matter? Not really—or not alone. Like Civil War, the poll doesn’t go into the rather important question of why Americans want to secede, or what they would want such a process to look like, or any of the practicalities of establishing newly sovereign governments afterward. I suspect that it, like the movie, was commissioned solely for the sake of provoking headlines, garnering buzz. And the national percentage of pro-secession respondents, though numerous reports suggested it was unusually high, is actually on par with what similar surveys have revealed for nearly a decade.

A more insightful survey was conducted (also by YouGov) for the Independent California Institute, whose director, Coyote Marin, reached out to me after reading Break It Up. What I like about the ICI is that it’s less a pro-secession advocacy organization like the Texas Nationalist Movement or the discredited, Russia-aligned Yes California group and more a think tank devoted to studying the underlying issues of how the Golden State benefits and suffers from its membership in the Union and how those material advantages and disadvantages would change if it somehow was able to peacefully detach itself from the United States. According to the ICI poll, 58 percent of Californians believe they would personally be better off if California peacefully seceded from the Union. An even larger percentage, 68 percent, would like to see California become a more autonomous region within the existing Union.

The more interesting question asked by the national YouGov survey has to do with the right of secession. Can states unilaterally decide to withdraw from the United States? This, as you may recall, was the reason the (first) Civil War began in the first place—yes, ultimately, slavery, but more proximately, the right of secession. The South wanted to leave, the North said they couldn’t, and they fought it out in a superbly bloody, continent-wide death-match for four years, resolving the question in the North’s favor—or so it seemed. Nobody has had the heart to try again.

But there are increasing signs, including but not only in this new YouGov poll, that America’s longstanding consensus on the question is coming under strain. According to the survey, 26 percent of Americans believe states do have the right to secede, while 35 percent say they don’t, and 39 percent say they aren’t sure.

Some months back, Nikki Haley—once a candidate for the American presidency, if you recall—was asked about the showdown between Texas and the Biden Administration. She answered, “If that whole state says, ‘We don't want to be part of America anymore,’ I mean, that's their decision to make.” She later walked back the comments, acknowledging, “The Constitution doesn’t allow for that,” yet the episode suggested some lingering confusion on the question—much more so than you would expect if the matter were decided at Appomattox, as one often hears, or in Texas v. White, the 1869 Supreme Court case that ostensibly resolved the issue once and for all by declaring the United States “an indestructible union.” As with so much nationalist rhetoric, that was more an earnest hope than a binding legality.

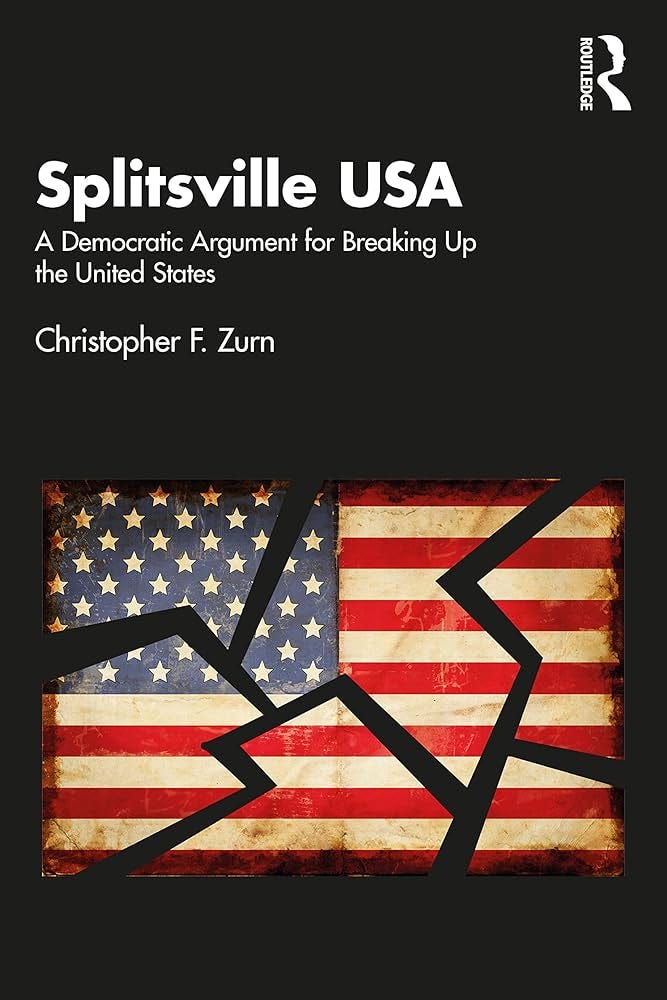

As I’ve said many times, I wrote Break It Up because I became fascinated by secession as a historical matter—who else besides the Confederates had this idea before?—and because there seemed to be something in the air in the late Obama era that indicated the idea of disunion might return to American politics with a vengeance. That happened sooner and more intensely than even I expected—so the book’s focus on the history ended up being both well-served and somewhat overtaken by events. I just hoped others would pick up on my historical themes and think more intensively and constructively about what secession might actually look like in the present. A new book does this well: University of Massachusetts philosophy professor Christopher F. Zurn’s Splittsville USA: A Democratic Argument for Breaking Up the United States. From now on, when interviewers ask me what a peaceful, negotiated break-up might actually look like, I’m just going to point them there.

How are you all? I hope well. Now here’s some reggae: