Crossing the Rubicon, Again and Again

Trump’s penchant for the use of armed force against citizens isn’t entirely outside the bounds of American history.

Today, the eyes of the political world are fixed on Georgia, but tomorrow they will revert sharply back to Washington D.C., where Congress is set to meet to certify Joe Biden’s victory in the presidential election. On the streets, thousands of conspiracy theorists will attend a planned pro-Trump “Stop the Steal” protest; there will likely be counter-demonstrators to meet and mingle with them. According to a bracing buried-lede in today’s New York Times, Pentagon officials fear “that Mr. Trump could seek to use civil unrest, especially if it turned violent, to use active-duty troops to restore order, which could play into his battle in Congress and in the courts to overturn the election outcome.”

Hundreds of DC National Guard troops have already been called up to monitor the proceedings. These troops, the Times noted, are ultimately under Trump’s command, as are many others that could be deployed as needed to the “battlespace,” to quote now-former defense secretary Mark Esper instructing governors last June on how to suppress massive racial-justice protests and return the country to “the right normal.” It will be a dramatic and perhaps a momentous day in the constitutional history of the United States.

In this context, Esper’s comment is worth returning to. Something fundamental and perhaps unalterable changed in the United States last summer. Unidentified troops—America’s own “little green men”—stormed peaceful protests in several American cities, throwing citizens at random into rented vans. In one frightening photograph, lines of heavily armored soldiers guarded a shuttered Lincoln Memorial. The president ordered the police to attack protesters outside the White House solely to secure a transparently opportunistic photo op. Our long-lingering “cold civil war” suddenly turned hot.

Commentators scoured the annals of history in search of analogies for the events of those weeks. Many compared the unrest to that of 1968, when assassinations and riots raised the possibility of a breakdown in order and helped usher in the era of conservative political dominance that has culminated in Trump’s undisguised brutality and unapologetic divisiveness. Others cited 1933, in Germany, when the Nazis used a fire at the Reichstag to seize total control over the paralyzed and dysfunctional government.

Perhaps a more apt parallel, however, is to a much earlier year—49 BCE, and a pivotal, infamous event marking the end of the Roman Republic.

That year, Julius Caesar led one of his legions across the Rubicon River, the traditional boundary between Gaul and Italy—thereby breaking a longstanding taboo against using military force within Italy itself. The ambitious general felt he had no choice. Following a string of daring successes, he had been ordered to return to Rome, where he feared facing trial for his unsanctioned military adventures in what we now call France. The Senate ordered him to disband his forces; he refused. Caesar knew his entrance into Italy with an armed guard would be a dangerous provocation. It sent the Senate fleeing from the capital, creating a power vacuum eventually filled, after a fierce civil war, by Caesar himself. The Republic never recovered and, despite Caesar’s assassination, eventually collapsed. A centralized monarchy, observing only the forms of popular government without the spirit, rose in its place.

This is the original meaning of the phrase “crossing the Rubicon”—not passing the point of no return to just any destination, but specifically using imperial forces against domestic opponents, and thereby bringing disorder, civil war, and authoritarian rule.

So, has America finally crossed the Rubicon?

For some observers last summer, that seemed to be the case. As the historian Joshua Zeitz wrote on Twitter in June, “A head of state using a standing army to occupy an American city, compel citizens off the street, stifle free expression and assembly—using paramilitary forces to smoke clergy out of their churches at the head of state’s whim—is pretty much the founders’ nightmare.”

Zeitz didn’t mention the Rubicon, but he may as well have. The founders of the American republic knew their Roman history well—military journalist Thomas Ricks has a new book out on this subject—and they knew to be on guard against an enterprising military chieftain in the Caesarian mold.

Yet for all the hand-wringing over Trump’s actions this summer, the depiction of his use of armed force against citizens as wildly outside the bounds of American history suggests a mistakenly starry-eyed understanding of the national past.

As readers of Break It Up know, a scenario closely fitting Zeitz’s worst fears actually came to pass only five years after the Constitution went into effect. Usually, this is called the Whiskey Rebellion—its opponents’ pejorative label. Frontier denizens of western Pennsylvania used liquor in lieu of hard currency, so when George Washington’s treasury secretary Alexander Hamilton pushed an onerous tax on the precious liquid, the settlers revolted. They painted their faces black and violently attacked not only tax collectors but anyone who paid them. Roaming bands tortured opponents and besieged officials in their homes, exchanging gunfire before burning buildings down. Some spoke of seceding from the United States, or marching east on the federal capital at Philadelphia. “The whole cry was war,” as one observer put it.

In response, Hamilton marched west at the head of thirteen thousand hastily-raised troops to viciously suppress the rebellion. He wanted to use the uprising to teach a lesson not only to the rebels but to all Americans: The federal government would not back down from a fight, even one with its own citizens. The soldiers arrested more than one hundred rebels, kept them in horrid conditions, and forced many to march east back to Philadelphia. Washington watched with satisfaction as the prisoners limped bleakly past the Executive Mansion.

It wasn’t the last time the military would be deployed against citizens. More than a decade later, Washington’s political opponents—the Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison—also opted to enforce federal law through military force. After a string of high-profile British insults to American ships on the high seas, President Jefferson asked Congress in 1807 to institute an embargo on all overseas trade. The move backfired, hurting the American economy far worse than Britain’s. The ensuing depression devastated commerce-dependent New England, the home-base of the Federalist political opposition. Yankees saw Jefferson’s “dambargo” as a secret plot to ruin New England. Some in the Northeast even began talking about breaking off from the Union, perhaps even rejoining Britain, to protest a government that clearly didn’t care for their interests. Citizens resorted to smuggling, that time-tested subversive tactic, to get around the trade ban. Gun-wielding mobs helped move goods across the Canadian border, while others liberated ships held by customs authorities in port.

Jefferson, a vocal opponent of centralized power in the 1790s when his rival Federalists were in power, now ordered the military to crack down on the New Englanders’ insurrectionist activities. The illicit trade with Canada, he wrote, “amounted almost to rebellion and treason.” He personally took charge of the enforcement of the detested embargo and even sent federal troops to aid the effort. As historian Gordon Wood has written, “The United States government was virtually at war with its own people.”

In the summer of 1877, labor strikes broke out in a railyard in Pennsylvania and spread along train lines all across the country. Yet “strikes” isn’t a fitting word for the raging battles that broke out between workers and their allies and state-backed private security firms. “Bread or Blood,” the protesters vowed. They formed picket lines, burned railroad property, set up barricades, dug trenches, and effectively shut down interstate commerce for weeks on end. The uprisings were remarkably popular. “Public opinion,” The New York Times observed, “is almost everywhere in sympathy with the insurrection.”

Railroad officials implored President Rutherford Hayes to send the military to suppress the strikes, and he complied. In response, the federal government deployed troops recently pulled from the Reconstruction South, where they would no longer be needed to defend black civil rights—not because those rights were no longer under threat but because it was no longer the policy of the federal government to defend them. Three thousand troops helped local militia and private agencies like the Pinkertons to put down the uprisings.

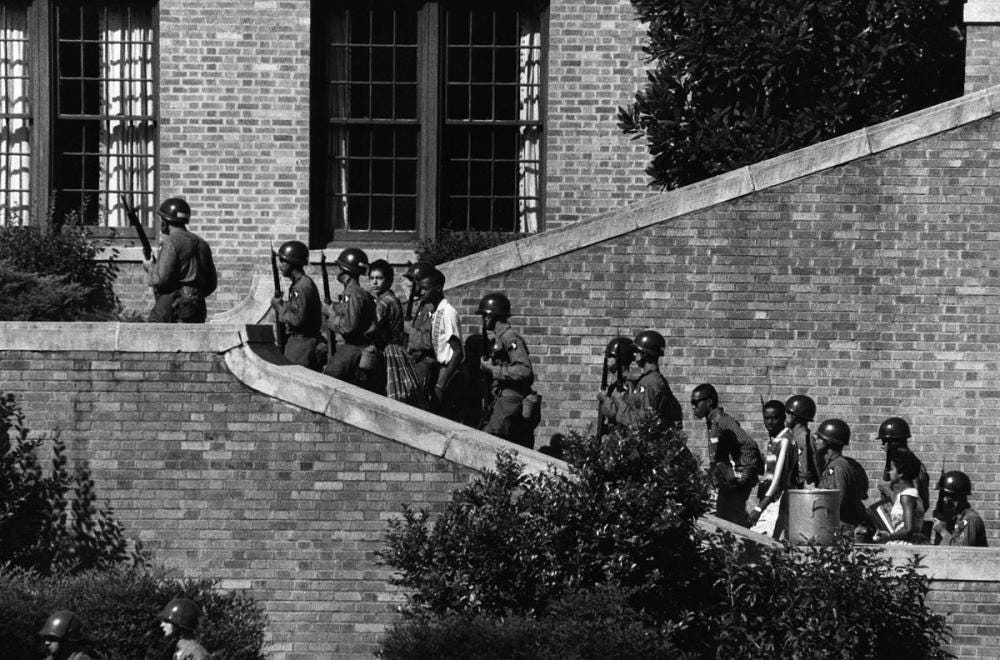

In 1933, the Army mobilized in Washington, D.C., and attacked encampments of World War I veterans asking for early pay-out of their promised bonuses to help them make ends meet during the Depression. (Dwight Eisenhower helped Douglas MacArthur clear out the unseemly eyesore.) And of course, the armed forces have at least once been deployed within the United States for noble purposes, as when President Eisenhower reluctantly sent the 101st Airborne to Little Rock, Arkansas, to escort black children past a mob of angry, expectorating whites to the attend city’s newly-integrated Central High School.

For all its disturbing echoes of the arrival of authoritarianism in other countries, it should be clear, given all of these long-forgotten episodes, that there is little that is truly new, in the U.S. context, about Trump’s deployment of federal forces against citizens—other than that it had never yet happened in the present century as it has in every previous one of this country’s ever-embattled existence.

Throughout its history—a far messier and much less exceptional story than we are given to believe—America has crossed the Rubicon again and again and again. The question we should be asking now is not so much whether the republic is about to fall, but whether it was ever a republic at all.