Making Sense of Marjorie Taylor Greene

My interview in The Atlantic; also, details on my new book project.

Hello, friends. It’s been quite awhile—well over a year. I’ve been busy raising two kids, buying and moving into a house, landing a new book deal and writing it (more below). I’ve also, to be perfectly honest, tried hard, with uneven success, to move on from the topic to which this newsletter is devoted, the topic to which I likewise devoted some six or seven years of my life: America’s little-known 400-year history of secession and disunion. What seemed like a really out-there, provocative idea when I first came up with it, around late 2014, came to be the subject of near-daily headlines, which, as I wrote in this Slate essay last January, was both intellectually satisfying and somewhat unsettling. I wanted to spend my time thinking about something else, thus the new book project (read on, I promise), and, largely, I have.

But the disunion theme just won’t go away. When the draft of the Supreme Court’s anti-abortion ruling was leaked last spring, the New York Daily News asked for my comments, which were published in a nice big spread in the print edition. Back in the city to see friends the weekend of my thirty-second birthday, I had the pleasure of picking up a copy on my way to take in a game at Yankee Stadium, as if it were 1922 instead of 2022. In any case, you can read that piece here.

I have also been called upon a few times to comment on the movement among citizens in several rural counties in western Oregon to leave that state and join their more conservative eastern neighbor, Idaho. While not exactly the subject of my book, which focused more on movements to secede from the Union entirely, rather than to create a new state or join an existing one, outlets interested in the history of separatism in the US more broadly have come knocking. Perhaps most excitingly, CBS Sunday Morning featured me in a segment about the “Greater Idaho” movement last fall (I’m on around 3:30). I wasn’t enormously pleased with the few lines they picked from our long and wide-ranging conversation, but the reach of the program became clear when I saw a sharp burst in book sales and visits to my personal website. More recently, a crew from the global branch of Japan’s state broadcaster, NHK World, came to my home to interview for a story they were doing on the same subject. I’m excited to see how our new built-in bookshelves, the kind we always fantasized about having in our home someday, play on camera.

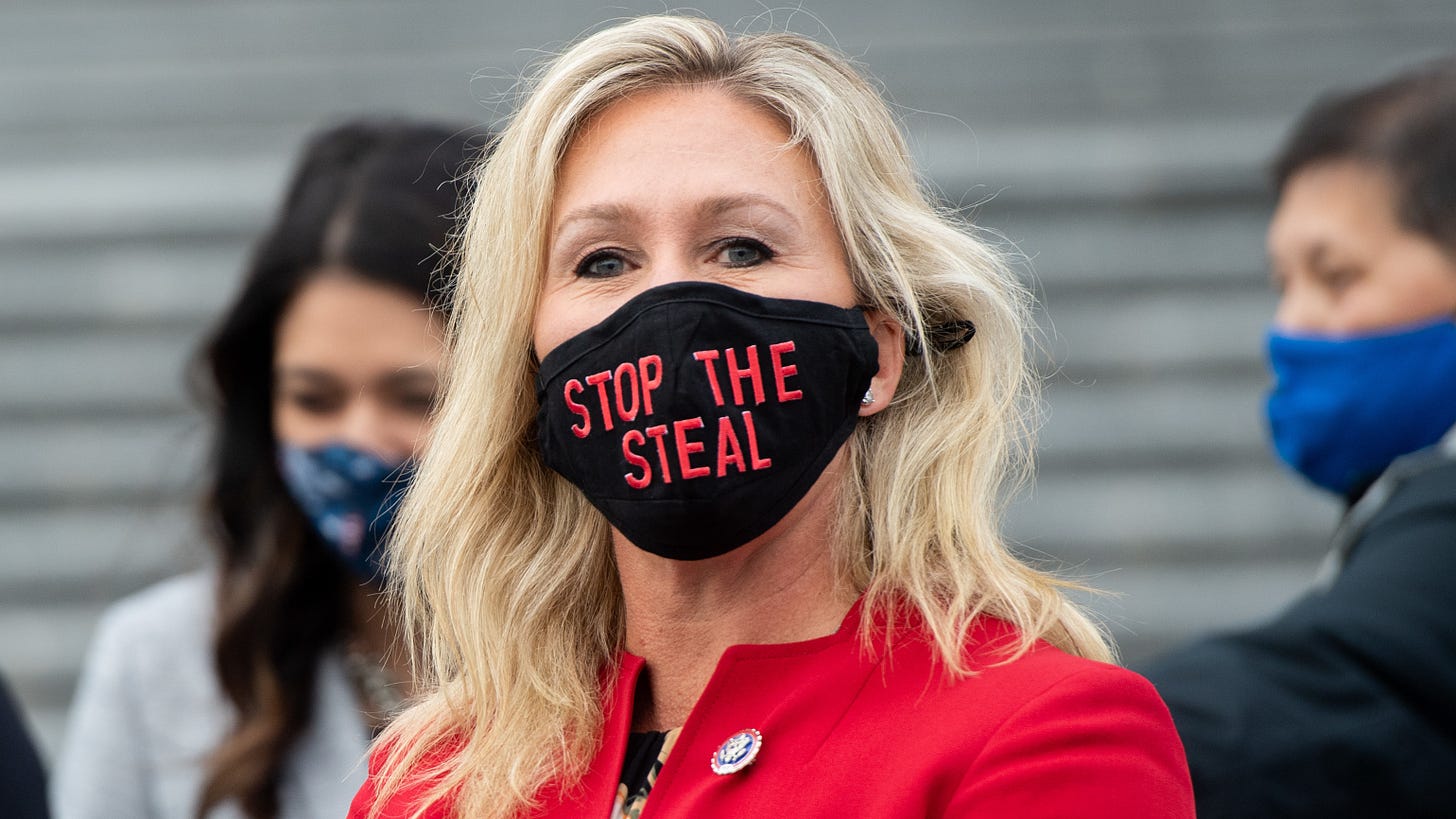

Anyway, the reason I’m finally posting something to this newsletter (is that even the correct way to phrase it?) is because The Atlantic interviewed me about the latest excuse everyone has to talk about what they say we shouldn’t ever talk about: Georgia congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene’s extended Twitter rant earlier this week promoting the idea of “National Divorce.” It’s not the first time the notorious attention-seeker has endorsed partition of some kind, so I wasn’t too interested. It was easy to avoid, as I quit Twitter in December—late-night doom-scrolling was hurting my brain, and I just wanted no part of whatever Elon Musk was doing with the site—but when The Atlantic came calling, I pasted the thread into a Google Doc and, crotchety old luddite that I am and have always been, printed it out to read.

I was stunned—not, as so many pearl-clutching commentators were, by the supposedly treasonous sentiments Greene espoused in the missives, but by the astounding idiocy displayed therein, as well as the gratuitous transphobia, the galling racism, the rotten-brain fixations on George Soros, “ESG,” drag queen story-times. Then there was the fact that her much-ballyhooed “National Divorce” proposal, read closely, did not actually argue for breaking up the country but returning to a form of federalism promoted by mainstream Republicans ever since Ronald Reagan. She simply wants to return much of the power wielded by the federal government to the states. She wants to cut the Department of Education. That is deregulation. That, as I told The Atlantic, is federalism.

So why wrap it in the language of disunion? Whereas Reagan took his neo-Confederate vision of states’ rights and a radically diminished national government and tried to smuggle it in under the seemingly benign branding of good old American conservatism, Greene seems to be going out of her way to do the opposite: advocate a fairly bland small-government ideology—still quite dangerous, don’t get me wrong, and explicitly racist—but use the sex appeal, as it were, of secessionism to sell it to a fired-up, gun-toting right-wing public. That says something about the salience of the idea among the American public, and not only on the right.

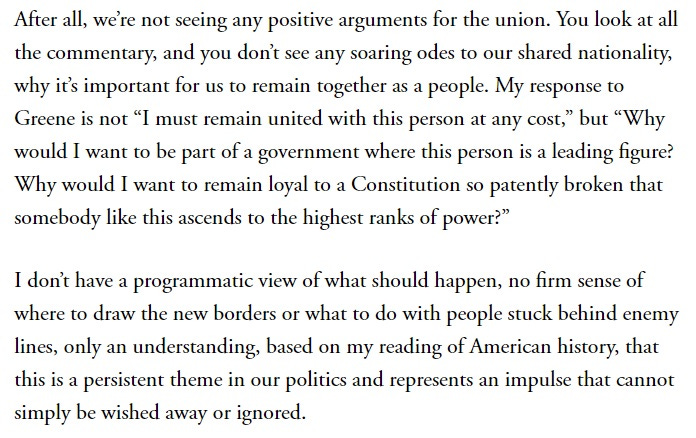

Far more distressing than Greene’s incoherent mouth-poop, I thought, were the outraged responses from mainstream opinionizers like The Atlantic’s own Peter Wehner and Ed Kilgore of New York magazine and from supposedly sensible Republican politicians like Utah Governor Spencer Cox. What one never heard in the torrent of ridicule and criticism heaped on Greene, what one likewise rarely hears on other occasions when the idea comes up, is any ringing defense of national purpose, pride in the unity of the nation, or sense of American mission, any suggestion that the Union remains, as Lincoln put it, “the last best hope of earth.” All we get are finger-wagging reminders, often delivered in the tone of a lament, that the obstacles to an uncoupling are too high, that there is no constitutional mechanism for such a dissolution, that our enemies would rejoice at our downfall. Is it indeed “evil,” as Cox said, to ask fundamental questions about the worth of the national enterprise?

The last two paragraphs of the Atlantic interview pretty much summarize my feelings:

The interview was published yesterday. It’s behind a paywall but I’ll link below to a PDF. I do recommend subscribing, however. I’ve been a print subscriber for most of the last decade and a half—drawn in, at first, by Christopher Hitchens’ back-of-the-book essays way back when. I cancelled my subscription late last year when I saw a cover story by a famous TV anchor, which seemed lame as hell. But I renewed last month when I kept hitting the paywall too often. Here’s the piece, but do consider subscribing.

About that new book. I sold the proposal last winter, but I guess never got around to informing you, my loyal legions. Grave and solemn apologies.

The book is tentatively titled No More Pharaohs, No More Slaves: American Jews, the Civil War, and the Struggle to End Slavery. Here’s the deal announcement in Publishers Marketplace:

My interest in this subject dates back even longer than with the subject of Break It Up. It all began with an essay I wrote for a class I took in college on American Jewish history. The essay was about Jewish abolitionists in the antebellum United States, some of whom opposed slavery for explicitly Jewish reasons, while others were totally detached from religion but still considered themselves, and were considered by others, to be Jews. I remained interested in the topic over the years, and published a version of that essay in The Forward in 2015, on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery throughout the US. Still, the topic would not let me go, however, and at some point after finishing Break It Up I began to research the question again, this time more broadly, encompassing not only Jewish abolitionists but Jewish slaveholders and pro-slavery propagandists, as well as rabbis and communal leaders who, nervous about the community’s already tenuous position in their adopted homeland, simply tried to stay out of the fray. The good, the bad, and the ugly, as I often tell people in my cocktail-party summation of what I’m working on. More broadly, the book will tell the story of what happened when one people defined in large part by a historical experience of slavery arrived and found refuge in a nation likewise defined by slavery. What if any connections did these early American Jews draw between their own oppression in the past—and, in the Europe they fled from, very much in the present—and that of Black Americans in the 19th century US? How did their Jewishness shape their encounter with slavery and the political debate over its future? How did their encounter with slavery and the crisis of the Union shape their Jewishness? And what happened when that struggle over slavery tipped the nation that had become their refuge into a deadly Civil War?

For a small taste of what I’m getting at, you can read this book review I wrote for Jewish Currents last winter, appraising a new biography of Judah P. Benjamin, the Confederate secretary of state and one of the main characters of my book. The others will be much less well-known, and it has been a real pleasure digging into their lives and writings and their often incredibly impressive actions.

I also want to note how lucky I am to have landed the book with Alex Star at FSG, someone whose work I’ve admired ever since he visited my internship class at The Nation, eleven years ago, and explained to us mere pups his vision of literary non-fiction and what makes a piece of true, source-based storytelling work. Ever since, from afar, I’ve looked up to him as a sort of guru of the kind of accessible, non-academic historical writing I like to read and hope to write. Alex edits many of my favorite writers on American history, such as William Hogeland, author of must-read books about the Whiskey Rebellion and the forgotten Indian wars of the early 1790s (I interviewed him for The Nation in 2017) and David Waldstreicher (whose new biography of the enslaved Revolutionary War era poet Phillis Wheatley I started this week and which, I must tell you, looks to be an absolute masterpiece). Along with the joys of rearing children and the literally infinite splendors of nature and history and general contentment I’m finding since we moved to the Hudson Valley in 2021, getting to work with Alex has been cause for not-infrequent pinches of my own arm as I ask myself whether this can all possibly be real.

I’ve been working like mad on this project and am unspeakably excited for you all to read it. At once the work is going much easier than last time around, since I now know what it takes to make a book—when to stop researching and start writing, how to shape a chapter—and much harder, with two littluns to get out the door in the morning and pick up from school seemingly about five or ten minutes later. I don’t know when it will be done, much less when it will be published, but you’ll certainly be the first to know.

Finally, just a reminder that if you can think of anyone who might enjoy Break It Up, please pick up a copy or two from Bookshop.org, which gives the proceeds directly to independent bookstores. I’m still very much hoping the publisher will put out a more affordable (and perhaps updated) paperback edition, and demonstrating that the hardcover continues to sell would be a great way to encourage them to do so.

Enough for now. Thanks for reading. Take care, everybody.